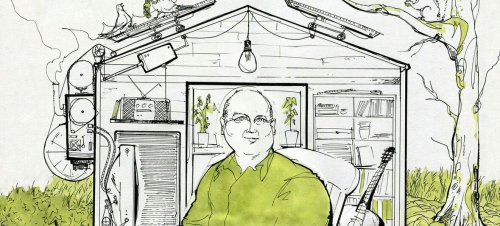

Louis de Bernières … shed matters

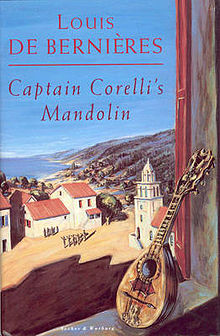

Louis de Bernières (born 8 December 1954) is a British novelist most famous for his fourth novel, Captain Corelli’s Mandolin. This was published in 1994 and won the Commonwealth Writers Prize for Best Book. It was also shortlisted for the 1994 Sunday Express Book of the Year. It has been translated into over 11 languages and is an international bestseller. A film version was released in 2001.

In 2009 he was a featured author in the Guardian’s Writers Rooms series.

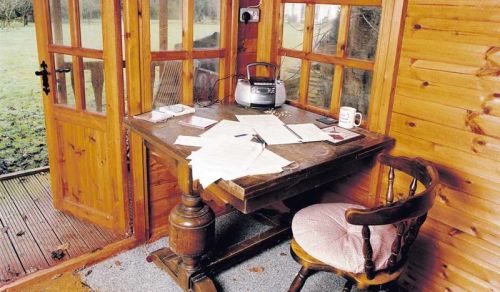

Anyone who works at home needs a refuge from the rest of the household, as far from the house as possible, and definitely without a phone. Mine is in one corner of the garden, overlooking a vegetable patch and young orchard, and I feel great happiness in it. I am hassled only by the cat – a catflap would reduce the inconvenience.

I installed a solar panel behind the shed, which supplies two enormous 12-volt batteries wired in parallel. The lights run off the 12 volts, but I have a magic box that converts it to 220 for my laptop and my little low-fi, with another that stops the current from reversing and discharging into the panel. I did this all myself, and was amazed at how much I remembered from physics classes at school with Mr Milner. Heating is by gas bottle and caravan heater – I got all my gadgetry from a caravan park near Great Yarmouth. I have to empty earwigs out of the lights and fittings, and spiders thrive even though I completely sealed the building with silicon bathroom sealant. Out of sight are a camping stove for brewing up tea, a music stand, a box full of croquet mallets and hoops, a CD rack and a bookshelf for reference books.

The clock is for reminding me how little time there is before lunch. The chair, inherited from my grandfather, has had my backside in it as I wrote all my novels. It is so comfortable that the cushion is superfluous. The table is from a junk shop. I like to write to music, hence the low-fi and CDs. I make notes and write poetry in longhand, in notebooks. The paraphernalia on the table concern a play I was writing about Handel, except for the dried-up daisies, which are the remains of a daisy chain that my son Robin made for me when he was three.

It is nice to look up and see the pheasants strutting about outside, but the best thing about the shed is its absolutely quintessential smell of sheds.

In 2016 he gave another interview, again for the Guardian, in which he talked about his writing day.

I’ve got two writing places. There’s a shed, next to the vegetable patch, which is a lovely place to write but I can get uptight about the pigeons and squirrels. I tend to write things in there that don’t need any research because you can’t keep many books in a shed or they go rotten. It’s powered by solar panels, which I fitted myself, and heated by a caravan gas heater. More often, though, I write in my library, which has thousands of books. I’ve also got absolutely stacks of notebooks, which makes my creative life a bit chaotic because I don’t know where to find things.

I write poetry longhand, often on trains, because poetry needs to be musical and it’s quite a help when you’ve got railway wheels going, “da‑da-dum, da-da-dum, da-da-dum …” Prose I usually write straight on to the computer. But I wrote my first novel, and some of Birds Without Wings, longhand. My poor sister used to type things up for me. Eventually, she gave me £500 and said, “Get yourself a word processor.” So my next three books were written on a Brother with a tiny black screen and green writing, which I called Esmerelda. It was actually my most fertile period, and I often wonder whether I should go back to Esmerelda. I still have her in the attic.

I avoid listening to vocal music when I’m writing or I end up listening to the words, at least if it’s in a language I understand. When I was writing Captain Corelli’s Mandolin I was listening to Greek and Italian music. I like writing to Ludovico Einaudi because he’s a bit like Bach: you can either treat him as wallpaper or listen very intensely.

When I was fuelled by black coffee and cigarettes I could write for 16 hours. Now I just do mornings and then life kicks in; things like fetching the children from school. Also, in Norfolk it’s hopeless: people keep calling in for cups of tea. I try to do a complete chapter in a morning, and then I tinker with it for the next couple of days. If I can do a chapter a week I’ll get quite a lot of books done. An author tour can really interrupt, but your publishers don’t actually want you to write too much, they can’t cope with it. And I do write too much. So they’re probably grateful when I’m away in some little stone town in the West Country talking. And I love it.

I used to do all the research in advance, but it all went terribly wrong with Birds Without Wings because I had mountains of notes and I couldn’t organise it in my mind. Now I just do the research as I need it. I don’t use the internet much, because having looked up things about myself I know how much of it is rubbish. I prefer phoning or emailing people and interviewing them. I do a lot of reading, after breakfast with my feet up on the table. And you have to travel a lot. I’ve never written about a place I haven’t been to, I would feel very cheeky doing that.

I’m currently working on volumes two and three of a trilogy, and I’m writing them both at the same time. I never write in a linear way; I just write what I feel like and then put it all together at the end. In a way, it is a bit bonkers, but when I get to do volume three it will save me an awful lot of work because I’ll have already done it.