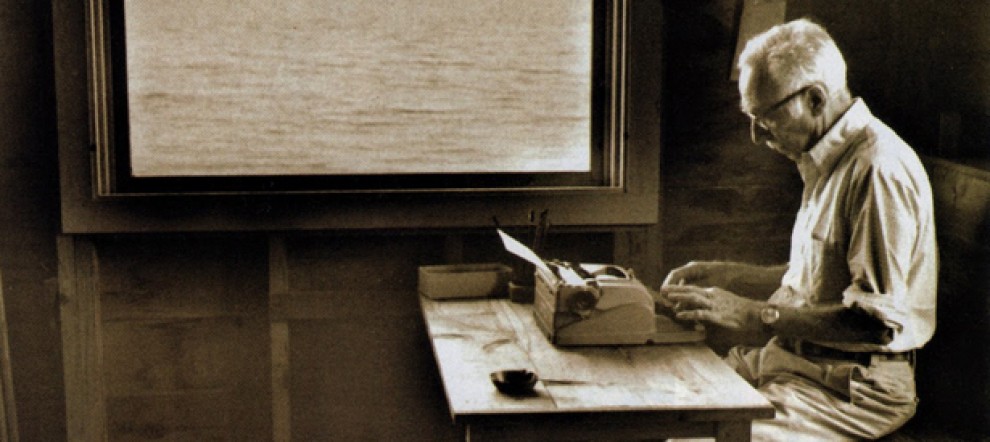

Henry Miller … a routine man

Henry Miller (1891-1980) was an American writer known for breaking with existing literary forms, developing a new type of semi-autobiographical novel that blended character study, social criticism, philosophical reflection, explicit language, sex, surrealist free association, and mysticism. His most characteristic works of this kind are Tropic of Cancer, Black Spring, Tropic of Capricorn and The Rosy Crucifixion trilogy, which are based on his experiences in New York and Paris (all of which were banned in the United States until 1961). He also wrote travel memoirs and literary criticism, and painted watercolours.

Miller was born in New York. After holding down various jobs he became employment manager of the messenger department, Western Union in New York. In 1922 he wrote his first book, Clipped Wings. Several years later he decided to devote his entire energy to writing. He travelled to London and then Paris, meeting other writers along the way such as T.S. Eliot and Dylan Thomas. He spent time with Lawrence Durrell on the Greek island of Corfu. He returned to America in 1940 where he continued writing and painting watercolours into his old age.

As a young novelist, Miller frequently wrote from midnight until dawn. While living in Paris during the 1930s, he shifted his writing time, working from breakfast to lunch. Then he would have a nap and write again until late afternoon and maybe into the evening. As he got older, though, he found that anything after noon was unnecessary and even counterproductive. As he told one interviewer, “I don’t believe in draining the reservoir, do you see? I believe in getting up from the typewriter, away from it, while I still have things to say.” Two or three hours in the morning were enough for him, although he stressed the importance of keeping regular hours in order to cultivate a daily creative rhythm.

In 1932-1933, while working on what would become his first published novel, Tropic of Cancer, Miller devised and adhered to a stringent daily routine to propel his writing. Among it was this list of eleven commandments …

- Work on one thing at a time until finished.

- Start no more new books, add no more new material to ‘Black Spring.’

- Don’t be nervous. Work calmly, joyously, recklessly on whatever is in hand.

- Work according to Program and not according to mood. Stop at the appointed time!

- When you can’t create you can work.

- Cement a little every day, rather than add new fertilizers.

- Keep human! See people, go places, drink if you feel like it.

- Don’t be a draught-horse! Work with pleasure only.

- Discard the Program when you feel like it—but go back to it next day. Concentrate. Narrow down. Exclude.

- Forget the books you want to write. Think only of the book you are writing.

- Write first and always. Painting, music, friends, cinema, all these come afterwards.

In addition, he split his day into three parts …

MORNINGS:

If groggy, type notes and allocate, as stimulus.

If in fine fettle, write.

AFTERNOONS:

Work of section in hand, following plan of section scrupulously. No intrusions, no diversions. Write to finish one section at a time, for good and all.

EVENINGS:

See friends. Read in cafés.

Explore unfamiliar sections — on foot if wet, on bicycle if dry.

Write, if in mood, but only on Minor program.

Paint if empty or tired.

Make Notes. Make Charts, Plans. Make corrections of MS.

Note: Allow sufficient time during daylight to make an occasional visit to museums or an occasional sketch or an occasional bike ride. Sketch in cafés and trains and streets. Cut the movies! Library for references once a week.

References:

- https://www.brainpickings.org/2012/02/22/henry-miller-on-writing/

- https://henrymiller.org/biography/#anchor2

- Daily Rituals by Mason Currey