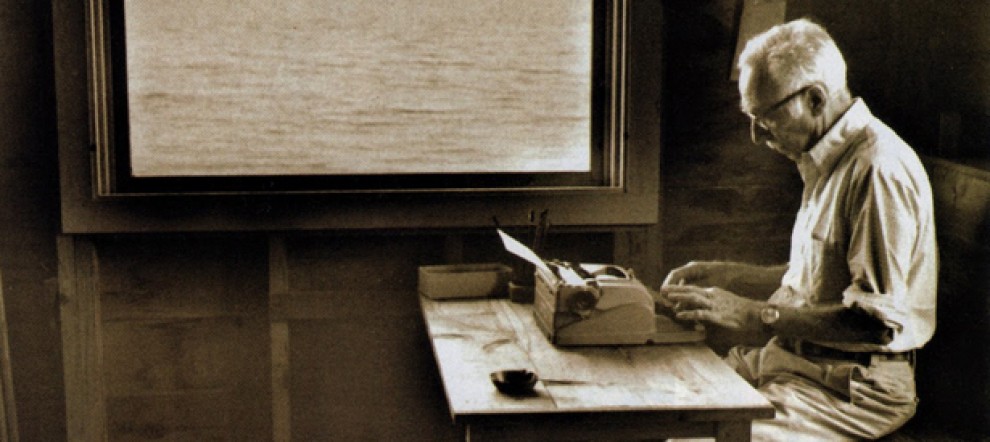

Graham Greene … the 500-a-day man

Graham Greene (1904-1991) was an English novelist and author regarded as one of the great writers of the 20th century. Combining literary acclaim with widespread popularity, Greene acquired a reputation early in his lifetime as a major writer, both of serious Catholic novels, and of thrillers. He was shortlisted, in 1967, for the Nobel Prize for Literature. Through 67 years of writings, which included over 25 novels, he explored the ambivalent moral and political issues of the modern world, often through a Catholic perspective. His most famous works include Brighton Rock, The Power and the Glory, The Heart of the Matter and The End of the Affair which are regarded as “the gold standard” of the Catholic novel. Several works, such as The Confidential Agent, The Third Man, The Quiet American, Our Man in Havana, and The Human Factor, also show Greene’s avid interest in the workings and intrigues of international politics and espionage.

Greene became a well-travelled man and his travels led to him being recruited by MI6. He also met Pope Paul VI, Fidel Castro and was good friends with Charlie Chaplin. He died in 1991 at age 86 of leukaemia and was buried in Corseaux cemetery, Switzerland.

In his 1951 novel, The End of the Affair, Graham Greene described what was in fact his own method of working.

“Over twenty years I have probably averaged five hundred words a day for five days a week. I can produce a novel in a year, and that allows time for revision and the correction of the typescript. I have always been very methodical, and when my quota of work is done I break off, even in the middle of a scene. Every now and then during the morning’s work I count what I have done and mark off the hundreds on my manuscript. No printer need make a careful cast-off of my work, for there on the front page is marked the figure — 83,764. When I was young not even a love affair would alter my schedule. A love affair had to begin after lunch, and however late I might be in getting to bed — as long as I slept in my own bed — I would read the morning’s work over and sleep on it. … So much of a novelist’s writing, as I have said, takes place in the unconscious; in those depths the last word is written before the first word appears on paper. We remember the details of our story, we do not invent them.”

In the summer of 1950, Michael Korda, a lifelong friend of Greene and his editor at Simon & Schuster happened to witness Greene at work on The End of the Affair. That summer Korda vacationed with Greene and others aboard a yacht called Elsewhere off the coast of Antibes. Korda was sixteen at the time, Greene forty-five. Korda later described watching the famous writer at work during this cruise.

“An early riser, he appeared on deck at first light, found a seat in the shade of an awning, and took from his pocket a small black leather notebook and a black fountain pen, the top of which he unscrewed carefully. Slowly, word by word, without crossing out anything, and in neat, square handwriting, the letters so tiny and cramped that it looked as if he were attempting to write the Lord’s Prayer on the head of a pin, Graham wrote, over the next hour or so, exactly five hundred words. He counted each word according to some arcane system of his own, and then screwed the cap back onto his pen, stood up and stretched, and, turning to me, said, “That’s it, then. Shall we have breakfast?” I did not, of course, know that he was completing The End of the Affair, the controversial novel based on his own tormenting love affair, nor did I know that the manuscript would end, typically, with an exact word count (63,162) and the time he finished it (August 19th, 7:55 A.M., aboard Elsewhere).”

Greene’s self-discipline was such that, no matter what, he always stopped at five hundred words, even if it left him in the middle of a sentence. It was as if he brought to writing the precision of a watchmaker, or perhaps it was that in a life full of moral uncertainties and confusion he simply needed one area in which the rules, even if self-imposed, were absolute.

In 1953, Greene was interviewed by the Paris Review for their Art of Fction series. He was asked if he worked regular hours when writing his books.

“I used to; now I set myself a number of words. Five hundred, stepped up to seven fifty as the book gets on. I re-read the same day, again the next morning and again and again until the passage has got too far behind to matter to the bit that I am writing. Correct in type, final correction in proof.”

In 1939, with World War 2 fast approaching, Greene began to worry that he would die before he could complete what he was certain would be his greatest novel, The Power and the Glory, and that his wife and children would be left in poverty. So he set out to write another book at the same time, a thriller that he knew lacked artistry but would make him money, while he continued to grind away at his masterpiece. So he rented out a private studio and devoted his mornings to the thriller The Confidential Agent and his afternoons to The Power and the Glory. To manage the pressure of writing two books at once, he took Benzedrine tablets twice daily, one upon waking and the other at midday. As a result he was able to write two thousand words in the morning alone, as opposed to his usual five hundred. After only six weeks The Confidential Agent was completed and on its way to being published. The Power and the Glory took another four months

Greene did not keep up this productivity, or the drug use, throughout his career. As he got older, Greene found it harder to maintain his clockwork discipline. Twenty years after that summer aboard the Elsewhere, Greene gave an interview to a reporter from the New York Times. Greene was then 66.

“I hate sitting down to work. I’m plugging at a novel now which is not going easily. I’ve done about 65,000 words — there’s still another 20,000 to go. I don’t work for very long at a time — about an hour and a half. That’s all I can manage. One may come back in the evening after a good dinner, one’s had a good drink, one may add a few little bits and pieces. It gives one a sense of achievement. One’s done more than one’s thought.

There are certain writers who seem to write like one has diarrhea — men like Durrell for instance. Perhaps their bowels get looser and looser with age. I’m astonished at someone like Conrad who was able to write 12 hours on end — it’s superhuman, almost. It’s like a strain on the eyesight. I find that I have to know — even if I’m not writing it — where my character’s sitting, what his movements are. It’s this focusing, even though it’s not focusing on the page, that strains my eyes, as though I were watching something too close.

In the old days, at the beginning of a book, I’d set myself 500 words a day, but now I’d put the mark to about 300 words.

The reporter added, a little dubiously, “Did he mean that literally — a mark after every 300 words? Precisely. With an x he marks the first 300 words, 600x comes next, 900x after 900 words.”

He admitted that, where he once required five hundred words of himself each day, he was now setting the bar as low as two hundred words.

He was asked if he was “a nine-till-five man.” “No,” Greene replied. “Good heavens, I would say I was a nine-till-a-quarter-past-ten man.”

References:

A marvellous writer and quite the chap, by all accounts. I like the 500 words a day rule. Everyone can manage that. Terry Pratchett also said that a writer should write 500 words a day, no excuses. It is so interesting to see how different writers ply their craft.

Isn’t it just! Greene took daily word count very seriously. I make a point of not having Benzedrine for breakfast as I much prefer grapefruit.

I like a nice bit of sausage and egg myself, but each to their own 🙂

I love a nice fry-up. But I have never been able to work out the term ‘all day breakfast’. After all, nobody says ‘all day supper’ do they.

Also, up here on the wrong side of the Wall, if you go into a chippy and ask for a single sausage, you get two. Same for a single fish. However, it doesn’t work when you ask for a single fiver in your change. Rant over.

Reblogged this on Have We Had Help? and commented:

On Graham Greene…

Thanks for doing this, Jack. Are you a 500-a-day man yourself ?

Between 250 – 500 Chris 😉

That’s realistic. About the same for me. Enid Blyton used to write 20,000 a day. God knows how.

I love graham greene

I read Power and the Glory when I was at school many years since. Such a fine and powerful writer.

yes, he’s so true to his characters. That is what inspires me to live in it. I thought it was old fashioned, but reading this made me stay on my course as a writer, to take my time with the characters and make them come alive. No use rushing, cause you’ll just mess up. I’m still to finish reading the heart of the matter, i’m anxious to know what Scobie gets up to

You are quite right. So many writers think they have to do it all in no time. Living takes time. So should writing. Have a good weekend. Chris.